Reading and maths…Quite often, a young child who struggles to read may be more able at maths or science. It is a great that they can add and subtract, observe patterns and discover the world around them. Then they hit ‘key stage 2’ in the UK – or a more advanced stage of primary education in other countries – and suddenly it all seems to go wrong. Why are they suddenly struggling with maths and science as well? Reading and maths in school can be very much connected…

What is going on with maths?

Very often, after the age of 7 or 8 years old, children are expected to be able to read. Their non-English subjects become literacy based and so weak literacy skills increasingly pull them down in other areas. Take maths: a child now faces ‘word problems’ which require reading and deduction before they even get to the ‘maths’. Take science: creative teachers will focus on practical science but at the end of the day, it is a brave teacher who avoids all written work. So our children who struggle with reading, now appear to struggle with maths and science.

How we can help with reading within maths and science?

Encourage science and maths

Firstly, we can ensure that their self-esteem and curiosity remain high in areas which interest them. Encourage them to watch documentaries and talk about them. Visit a science museum. Play number games which only require you to think and say, rather than read and write. Are they the fastest in your family at times tables?! Play games which focus on spatial awareness and patterns.

School support

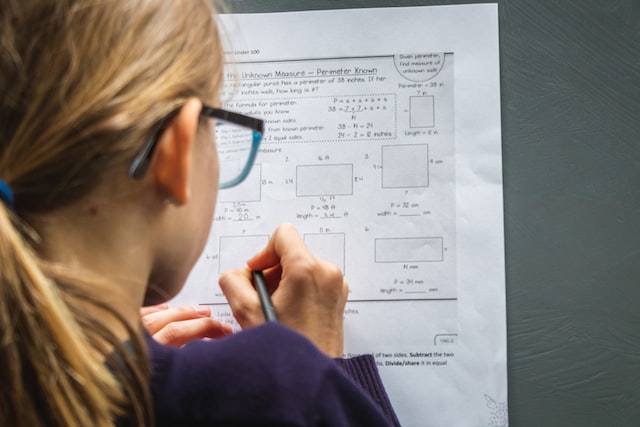

Secondly, ask if they can be supported with their literacy at school in these other areas but ask the teacher (and assistant) to differentiate between literacy support and maths support. This may not be possible but it’s worth a polite conversation. Too often, children who have poor literacy are automatically put in the low ability group because they need support. But they might only need support with the reading aspect of the work. This may be different to children who need help with maths concepts. So for example, this might be about supporting a child to read a maths problem, asking them to identify the operation needed and then leaving them to get on with it. Or it might be asking a child about a science concept and then scribing their observations.

Even with fabulous teaching, children who struggle with reading can inadvertently be asked to spend a disproportionate amount of time (and brain power) on their reading and writing during a maths lesson.

Teach vocabulary

Thirdly, explicitly teach key vocabulary. Whilst many children will understand that a ‘sharing’ maths problem will involve division if asked in isolation, some children struggle to locate the key word in a word problem. Teach these key words and frequent maths concepts like you would teach them times tables. Look at scientific words so that they become familiar with the before their science topic starts at school.

Other children become distracted by understanding irrelevant details or even pronouncing a name.

Hugh returns to Sheffield 2 hours after Phoebe has left. Phoebe left at 5.30pm. What time does Hugh arrive in Sheffield?

Hugh? Phoebe? Sheffield? Returns? If it is a name with a capital letter, they only need consider the letter (assuming there are not two the same!). Remember as the word problems get longer and more complex, the art of understanding them – and memory requirements – gets greater.

However, even short word problems can be problematic and require inference. Jen wants to go to a party and has £10 to spend on as many sweets as she wants. Which sweets could she buy from the selection below? The implication is that she will spend all her money and the pupil must work out what they can buy with £10 but no more. But some students might just choose their favourite. Or they might think that £10 is too much to spend. Maths problems do contain inference norms too.

Use visuals

Fourthly, use visuals or actual ‘things’. Draw a picture of the train arriving in Sheffield with an arrow and a girl leaving and a boy arriving. Grab three bowls and divide up some cornflakes in each to represent a division (or ratio) problem. Help them embed the learning in their heads, rather than become fixated on the words.

Acknowledge it

Fifthly, depending on the maturity and self-awareness of your child, consider acknowledging the difficulty. It is frustrating that the reading is holding them back – and annoying that the biology worksheet contained so much reading when the practical was so fun. It is complicated reading these maths problems and trying to work out what to do…

Finally…

Remember that for children who really struggle with English and writing, this is arguably the hardest stage. As they get older, technology should increasingly help with at least some of the issues. So keep their self-esteem high!

Do get in touch if you’d like to discuss any of the above.